A New Dialogue on Dementia

In this excerpt from his book, Dementia Beyond Drugs: Changing the Culture of Care, Second Edition, Dr. Al Power re-frames the barriers and stigma of dementia-as-tragedy into a new dialogue.

Diabetes versus Dementia

Imagine for a few moments that you have been diagnosed with diabetes. I am choosing this disease because it is a common condition about which most of us have a fair degree of awareness. It is incurable, but treatments are available. Many people live many years without serious problems, but many people may experience progression of the disease or develop serious and life-threatening complications.

Imagine that you are not feeling quite right, and so you visit your physician to find out what is wrong. After an examination and some testing, the doctor discovers that diabetes is likely the culprit. Of course, any new diagnosis can lead to emotional upset. There is a realization that your body is changing, that you are no longer free of illness, that you may need medication and will need to change your lifestyle. The disease could affect your life and longevity in many ways. Now let’s add another wrinkle to the scenario. How would you feel if your doctor insisted that your spouse, son, or daughter accompany you to your follow-up visit? The doctor speaks to your family member instead of directly to you, and says:

Your loved one has diabetes. This is an incurable and progressive disease; everyone who is diagnosed with diabetes will die. I think that you need to start thinking about planning for when your loved one can no longer do things without assistance and start talking about advanced directives for end-of-life care.

I doubt that most people receive the news of diabetes in such dire terms. And yet this is common when someone receives a diagnosis of dementia, even when it is in its very early stages.

Dementia-as-tragedy: Barriers and Stigma

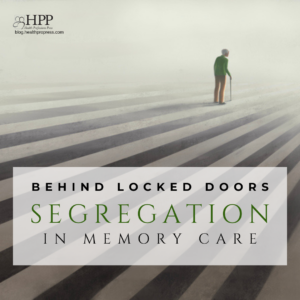

Next, imagine that, as a result of this single doctor visit, people start treating you differently and include you less in activities and family decisions, even though you want to participate. “The loneliest thing in the world is to be standing when everyone around you is sitting . . . and they all look at you and ask, ‘What is wrong with her?’” These are the words of Diana Friel McGowin, who documented her own experience with the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in her book Living in the Labyrinth.

Finally, imagine that from this day on, everything you do, from driving your car to paying your bills, is being scrutinized closely, and if there is the slightest slip—the fender bender we have all had to deal with, the occasional late bill payment, the inability to name a familiar song—you are in danger of having your independence taken from you.

It is hard to imagine these things happening to a person living with diabetes. They happen every day to someone with a new diagnosis of dementia.

I am not suggesting that a person who can’t remember her children’s names is capable of driving a car. But dementia is a powerful label that starts a long slide into a world of disempowerment, often long before abilities are lost.

Indeed, our prevailing view of dementia is that it is tragic, costly, and burdensome. Even as Alzheimer’s advocates campaign for more funding and resources, there is a tendency to express the urgency of the need by emphasizing the tragedy of dementia and relying upon stigmatized descriptions of the person. I have heard the very people and organizations who are charged with supporting those with dementia describe the condition as a “living death,” “the long good-bye,” or “the worst illness a person can have.” One highly touted educational course for professional caregivers states in the opening pages of the syllabus that “the person will slowly disappear,” and the syllabus makes several other stigmatized pronouncements, including that new learning cannot occur; that memories cannot be reawakened; and that people with advanced cognitive changes cannot make choices and the caregiver must “take over.” Unfortunately, such characterizations only create additional barriers and burdens, and dehumanize people in the process.

A New Dialogue

The dementia-as-tragedy dialogue increases public fear of the disorder, which is a barrier to education. It also heightens the stigma of the disease, which is a barrier to seeking early detection. After all, who would want to be diagnosed, knowing they will be treated like less of a person when the results are in? For doctors and other care professionals, this view of dementia causes us to see people primarily for their illness, rather than as unique individuals who happen to share a diagnosis. For researchers and the entities that fund them, it puts most resources into seeking the “holy grails” of prevention and cure, while comparatively few resources are devoted to helping improve the lives of those millions of people who live with dementia that will neither be prevented nor cured.

It is time for a new dialogue on dementia.

Read the book!

Dementia Beyond Drugs

Changing the Culture of Care

Second Edition

By G. Allen Power, M.D.

Copyright © 2017 by Health Professions Press, Inc.

Revolutionize the way you provide dementia care with this empowering guide to achieving culture change—now in its second edition!

Add comment