Starting with the Person: The Life Story and Human Rights

By Virginia Bell and David Troxel

The Best Friends™ approach has been shaped by real people—people with dementia we have been privileged to meet and work with over the years. One of our earliest and most important “teachers” was a college friend of Virginia Bell. Rebecca Riley was a nurse educator who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in her 50s. As she traveled what we now call the continuum of care—from home care, to day center care, to residential care—we were happy to share almost all of the dementia journey with her, including hundreds of hours spent together at the Best Friends™ Day Center.

Being a Best Friends care partner to Rebecca came very naturally to Virginia because the two women already were friends. The strong relationship between them was a starting point for a long journey. Even during rough moments, Virginia and Rebecca were able to draw on their long-term friendship.

What we learned from her early years with us was integral to the development of the Best Friends approach, including that:

We are more than just our memory and cognition.

Despite profound losses, there was still a person there with likes and dislikes, opinions and feelings.

Each person with Alzheimer’s is a unique individual.

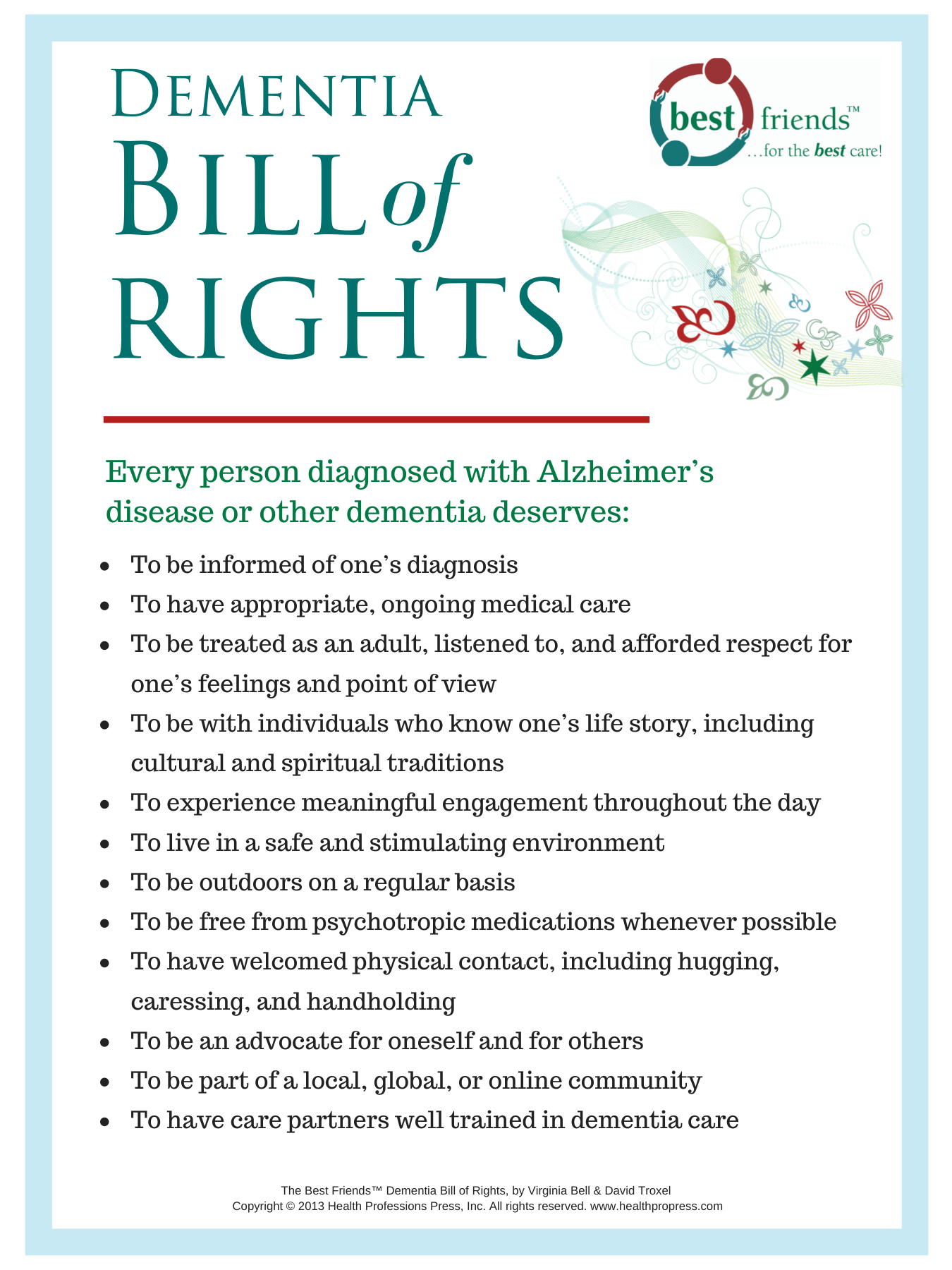

As Virginia likes to say, “When you’ve met one person with Alzheimer’s, you’ve met one person with Alzheimer’s.” Our desire to honor individuals and their rights became the starting point of our Best Friends™ Dementia Bill of Rights.

Alzheimer’s.” Our desire to honor individuals and their rights became the starting point of our Best Friends™ Dementia Bill of Rights.

Life Story matters.

From her family’s diligent efforts to provide Life Story information and from her long history with Virginia, we know so much about Rebecca. When she was having a bad day, we would “dip into the reservoir” and come up with just the right story, topic, question, or activity that pleased her.

Empathy is important.

Even when Rebecca had angry moments, we recognized that it was the disease talking, not something we should take personally. The behavior was caused by the symptoms of dementia, not because Rebecca was being deliberately mean.

Productive and interesting activities keep people connected and engaged in life.

At the day center, Rebecca gravitated toward more adult and purposeful activities, particularly ones that involved helping others. She also valued the unstructured times when she could share smiles, hugs, and short conversations and even just sit out in the garden watching the world go by.

Communicate, communicate, communicate.

Even when her language skills began to falter, Rebecca loved when our day center staff and volunteers would ask for her opinion, talk to her about the day, and communicate with her nonverbally through lots of hugs and smiles.

Stages of dementia can be arbitrary and limiting.

Families and persons with dementia want a general understanding of the overall spectrum of dementia and their place in it. Although staging can be a valuable tool for clinicians or research trials, we realized that Rebecca and other Day Center participants supposedly in the same stage of the disease process had different personalities, strengths, and abilities. Rather than focusing on stages, we focused on each individual and his or her own unique journey.

In many ways, socialization is the treatment for dementia.

Dementia is a disease of isolation. Little by little, persons with dementia step away from—or are excluded from—the world around them. Rebecca felt less alone at the fun-filled, relationship-centered day program where volunteer and staff provided her with love and friendship.

As a staff member working with older adults, you have probably met people like Rebecca—the person who has long been considered a brilliant lawyer, dedicated mom, or caring grandmother but who now struggles to put on a sweater or participate in a simple word game. How can you address her frustration and anger when confusion and forgetfulness happen? How can you encourage her to take part in activities and be a part of life? How can you help her feel safe, secure, and valued? How can you support her basic rights?

Focus on the person, not the task.

The answer is to focus on the person, not the task. The core of the Best Friends approach is simple: Treat the person with dementia as if he or she is a Best Friend. Like a friend, bring your knowledge of his or her Life Story and personal quirks and preferences to every interaction. Communicate sensitively, engage in fun and meaningful activities together, and try to bring out the best in the person instead of merely “managing” his or her disease. Use the idea of friendship to build a relationship and connection and to help the person overcome the isolation and fear that can accompany dementia.

This post was excerpted and adapted from The Best Friends™ Approach to Dementia Care, Second Edition by Virginia Bell and David Troxel. Copyright © 2017 by Health Professions Press.

Learn about the Best Friends™ approach!

What people experiencing memory loss need most of all is someone dedicated to helping them feel safe, secure, and valued—at all stages of the disease. Adopting the internationally acclaimed Best Friends™ approach to dementia care helps professional and family care providers gain the skills and confidence needed for this critical role.

What people experiencing memory loss need most of all is someone dedicated to helping them feel safe, secure, and valued—at all stages of the disease. Adopting the internationally acclaimed Best Friends™ approach to dementia care helps professional and family care providers gain the skills and confidence needed for this critical role.

Learn more about Best Friends™ products, training, and additional services at bestfriends.healthpropress.com.

Add comment