5 Inspiring Stories of Meaningful Person-Centered Memory Care

Small Ways Care Partners Have Improved Quality of Life and Made a Difference

This post was excerpted from Getting Dementia Care Right: What’s Not Working and How It Can Change by Anne Ellett, M.S.N., NP. Copyright © 2023 by Health Professions Press.

I have had so many meaningful experiences over the years working in memory care. I have worked with countless wonderful support partners and leaders, people who took the time to listen to an individual resident, advocated for him or her, and provided a gentle touch at just the needed moment to improve that person’s day.

The following stories are simple examples of best practices that are not necessarily elements of a large, organized culture-change project. The majority are the actions of one person or a small group of respectful support partners and leaders working to enable a resident to have a good day. However, each of these actions has helped move the culture forward. These stories demonstrate the benefits of taking the time to develop a relationship, learn what would be meaningful to an individual resident, and then advocating for the change.

Lemonade Among Friends

At an assisted living community I visited in Florida, the care partners noticed that residents loved watching the children walk by on their way home from school. Staff members placed chairs on the front porch so residents could be comfortable while waiting for children to pass by. As the weather got warmer, a support partner had the idea of making fresh lemonade to give to the children. Residents spent an enjoyable time each warm day squeezing lemons and stirring in the sugar. A table with umbrellas was set up at the edge of the lawn, and residents handed out small cups of fresh lemonade for the children to enjoy as they walked home. Some of the children were accompanied by their parents. Over time, people engaged in conversation with each other and shared stories. From these initial encounters over lemonade, some of the families became friends with the people who lived in the community. The children and their parents began to stop by and visit the residents, and residents were invited to school events, such as musical and drama performances.

Good Food for All

The dining program at a nursing home in Michigan was very stylish and had achieved high satisfaction ratings from the residents. Two choices of entrees were available for every meal, as well as a cook-to-order menu. Many meals were offered buffet-style so residents could make their own choices. The chef presented cooking demonstrations two times a month and had a list of each resident’s favorite dishes, which he would prepare frequently. However, this dining program did not extend to the locked memory care unit where 19 residents lived. Their meals were brought back on a large meal trolley, and only one entrée was made available. There were no cooking demonstrations or buffet-style meals. Residents did not get to make their own food choices. Several residents were on pureed diets and thickened liquids, and their meals were especially unappealing. Residents and their family members had made numerous complaints about the quality of the meals in the memory care unit.

A new administrator decided to improve the dining program for the residents living with dementia. For 4 weeks, the support staff and the administrator met together to brainstorm on how the dining program could be changed. Two meetings were held with family members, and each resident was interviewed individually to learn more about his or her preferences. The administrator met with the speech therapy staff to share the goals of creating normalcy and enabling each resident to have the right to determine his or her own food and liquid choices. Within 3 months, the chef started cooking demonstrations in the memory care unit two times a month, and buffet-style dinners were offered two times a week. Other meals were still transported in a meal trolley, but a variety of entrees were available. The chef promised to learn the favorite foods of each of the residents and make them available.

Telling Stories

A high school senior English teacher gave her students the assignment of visiting residents from a local nursing home and writing about their lives. Each student visited a specific resident a minimum of three times, learned about the person’s life achievements and adventures, and if possible, brought photos from the resident’s life for a class presentation. On the days of the presentations, the residents accompanied their students to class. Participants laughed and cried as the students told the life stories of the residents. One student’s presentation was accompanied by a soundtrack of the resident’s favorite tunes, and another student’s entire presentation was made up of jokes that he had learned from the resident!

Yoga in the Park

An assisted living community had a yoga instructor who led the residents in yoga every week; however, she did not lead any classes in the locked memory care unit. A nurse advocated for the residents living with dementia to join the classes, and many of them began to participate. The nurse then advocated for the memory care residents to join the yoga instructor for a weekly outing to the park across the street. Most of the memory care residents were eager to go to the park, and the staff set up chairs for an outside yoga class. As the residents living with dementia did their yoga, passersby would often stop to watch. Soon, the staff started bringing extra chairs, and anyone walking by could join the class. Some weeks, as many non-residents participated as residents. Every week, someone would comment, “I can’t believe they have dementia,” which would create opportunities for conversations about the abilities of people living with dementia.

Gone Fishing

At an assisted living community in Arizona, a support partner wanted to take some residents fishing at a nearby lake. He himself was an avid fisherman and thought residents would enjoy the experience. The assisted living community did not currently have a van for transporting a group. It was also short-staffed and could not spare multiple staff to leave on an outing.

The son of one of the residents volunteered to assist with the planning for the fishing trip. He contacted a local outdoor equipment supply store and met with the manager. The manager volunteered to fund the day trip from the store’s marketing budget. The store had a large van they could use, but it did not have space for the wheelchairs. Ten residents rode in the store van, and two residents were driven by the support partner in his car. The administrator drove his car with the two wheelchairs and an additional support partner. Volunteers from the store brough fishing rods and other needed supplies, and the administrator brought a picnic lunch and water. Four residents caught fish, and all of them were able to enjoy the day and put their feet in the lake. It was a special day, and they made plans to make it an annual event.

Keep Going

Culture change can seem overwhelming; I hear that all the time. As shown in the story “Lemonade Among Friends,” though, change does not always have to result from a “problem” situation. Sometimes, we can simply be alert to opportunities to make life better for the people we support. All of us have success stories in which something we did changed a resident’s life for the better, so I know that culture change on a large scale is possible. We are on the path; with inspiration from each other, let’s keep going.

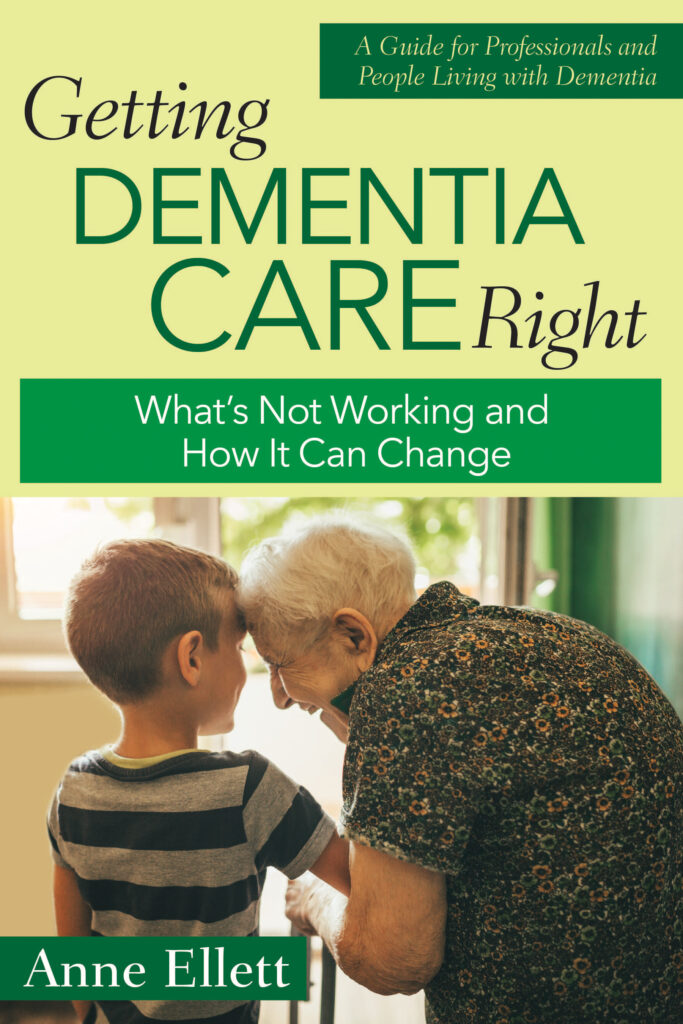

For more inspiring stories of person-centered care and best practices, get your copy of Getting Dementia Care Right: What’s Not Working and How It Can Change, by Anne Ellett, M.S.N., NP!

Read the book!

Getting Dementia Care Right

What’s Not Working and How It Can Change

By Anne Ellett, M.S.N., NP

Take a journey with Anne Ellett through a landscape of successful dementia care that is entirely possible yet too rarely seen in current care settings. Her encouraging descriptions of realistic, actionable practices will help set a course for positive change in the lives of residents and care staff alike.

While acknowledging common obstacles to progress—ill-informed attitudes, staffing limitations, organizational pressures, surplus safety concerns, and more—Ellett describes both large and small strategies for overcoming these challenges to produce big changes in the lives of residents with dementia.

Add comment