Can We Achieve Drug-Free Dementia Care?

It may seem unrealistic to expect that we can care for people without using any psychotropic drugs for their various expressions. What is clear, however, is that a new approach to dementia can drastically reduce the use of these medications, making them the exception rather than the rule.

We have seen a similar learning curve with the use of physical restraints in nursing homes. Due to the tireless work of pioneers, including Carter Catlett Williams, Lois Evans, and Neville Strumpf, these once-common features of nursing homes are rapidly disappearing. Many nursing homes are now restraint-free; I have not personally ordered a physical restraint in the new millennium. Could antipsychotic use in dementia become the “physical restraints of the 21st century”? My hope is that a similar learning curve will lead to the equally rapid removal of these drugs from daily use.

Make no mistake—this is hard work. It takes the combined efforts of many people to transform a model of care and constant vigilance to prevent the phenomenon of “institutional creep” that attempts to pull us back into the status quo. And yet, the potential benefits are enormous—not just the expected clinical improvements and cost savings (billions in unused antipsychotic pills alone), but also the improved well-being of millions of people who live with dementia, their care partners, families, and friends.

There will always be naysayers who will cling to the status quo and complain that such a change is too difficult, too expensive, too risky. In what he calls “the myth of perfection,” Bill Thomas (2008) describes the tendency of such people to look for the exception as a means to reject the entire model. I hear this all the time: “Well, it all sounds good, but how about Mrs. X? There’s no way you could treat her without an antipsychotic!”

The answer of course is, “You’re right—not in the world she is living in today.” That’s why we have to create a new one for her. Doesn’t she, don’t we all, deserve it? If there will be more than 100 million people in the world living with dementia by 2050, we had better get it right!

I was visiting my late friend Dr. Richard Taylor at his home in Houston in November 2014. At one point in our conversation, I asked Richard what core message he was trying to convey to people at the time. He thought for a moment and began to respond that we need to see the “humanness” of people living with dementia. Then he made a remarkable statement: “I believe that as people progress with dementia, their humanity increases.” This statement is remarkable to me because it runs counter to the prevailing view of dementia in society—one that, sadly, is all-too-often promoted by the medical profession, the media, and advocacy organizations—that the person fades away and becomes less human over time. But what Richard was saying is that while memory and language become challenged and our social roles and the pretenses we adopt in life may fade from view, our true essence is revealed. This, then, is the challenge that Richard posed to society: We have lost the humanity in our biomedical approach to caring for people living with dementia. How shall we restore it?

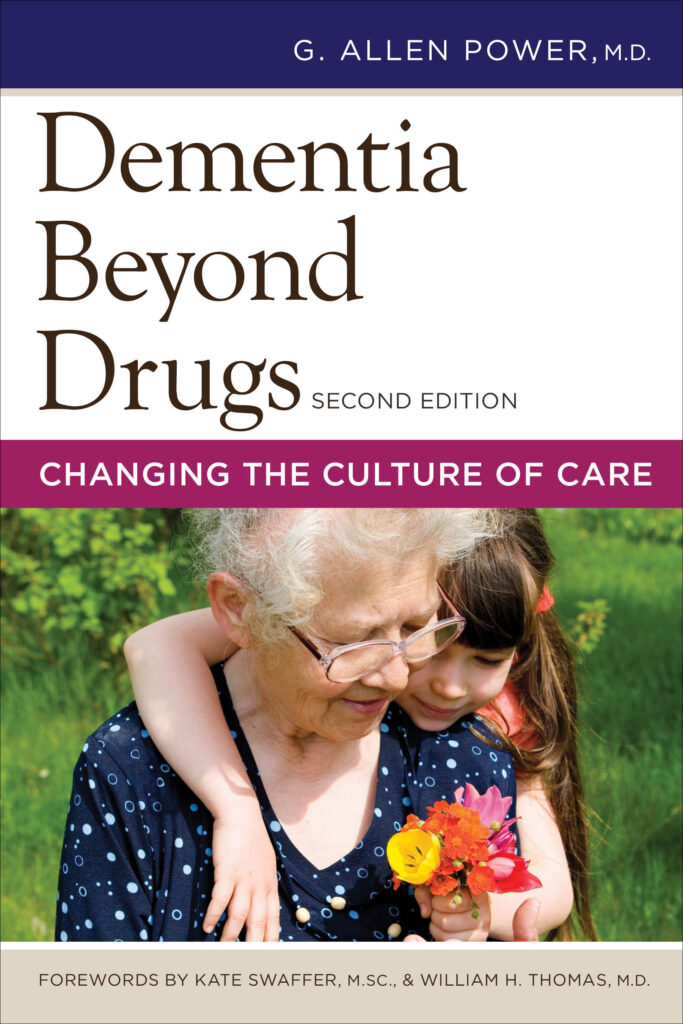

This post was excerpted from Dementia Beyond Drugs: Changing the Culture of Care, Second Edition by G. Allen Power, M.D. Copyright © 2017 by Health Professions Press.

Read the book!

Dementia Beyond Drugs

Changing the Culture of Care

Second Edition

By G. Allen Power, M.D.

Reducing the use of psychotropic drugs in the symptomatic treatment of dementia is key to successfully implementing compassionate, person-centered practices in your organization—and this book shows clearly why and how it can be done. The revised second edition of this award-winning resource introduces new research, language, and examples to reinforce the core message that antipsychotic medications are not the solution to ease the distress experienced by individuals living with dementia. Outlined here is the information and inspiration you need to provide alternative solutions for individualized support and care.

Add comment